The Extended Interview

Internships provide on-the-job training and entry into an employer’s world

By Anita Cirulis

JONATHAN LIU

Elizabeth VanOort helped find legal representation for immigrant children while interning in Washington, D.C., as part of the American Studies Program. Now she has a master’s degree in social change and is moving to Dallas to work with that city’s immigrant and refugee population.

Internships were in the news this spring when a 28-year-old former intern sued the Hearst Corporation, publisher of Harper’s Bazaar, for violating federal and state wage-and-hour laws. For four months in 2011, Xuedan (Diana) Wang worked 40 to 55 hours per week for the fashion magazine—all without pay.

“Unpaid interns are becoming the modern-day equivalent of entry-level employees, except that employers are not paying them for the many hours they work,” her lawsuit said.

According to Ross Perlin, author of Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy, there are approximately 1.5 million internships available in the U.S. each year, half of which are unpaid, saving companies approximately $600 million annually. Perlin says the number of unpaid internships grew during and after the recession as employers tried to compensate for tighter budgets—and laid-off workers, eager to fill gaps in their resumes, were more than willing to trade free labor for a foot in the door.

Employers have been required to pay their employees at least the minimum wage since the Fair Labor Standards Act became law in 1938. It wasn’t until 2010, however, that the Department of Labor clarified how the act applies to internships. The government identified six criteria that must be met before individuals participating in for-profit private-sector internships can do so without compensation. Among them: the internship must provide educational training, benefit the intern, and not displace regular employees.

Bill Minnick, director of Northwestern’s Career Development Center, helps place student interns. The college’s internship program, he says, is an extension of the learning that takes place in the classroom. While not all internships are paid, they almost always are taken for credit—and when they are, come with guidelines, support and goals.

Bottom line, Minnick says: “Internships are immensely valuable for students.”

Intern Expert

Ann (Vander Kooi ’88) Minnick’s experience with internships spans that of student, employer and educator. A communications major at Northwestern, she interned at St. Luke’s Hospital in Sioux City, Iowa, the summer after her junior year. At the end of the summer, they offered her a job. She turned it down to finish college, but after she graduated, she applied for a position at Grinnell (Iowa) Regional Medical Center.

“The CEO had worked with my boss,” Minnick recalls. “He saw my internship supervisor’s name on my resume, called her up, and asked if she would hire me. She said, ‘Oh, absolutely.’ I was 22 years old. Based on my internship, I got my first job.”

Minnick’s career in health care administration also involved marketing and public relations work for the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Avera McKennan Hospital in Sioux Falls, S.D., and Orange City Area Health System. “I’ve worked with interns in all my jobs,” she says. “Because Janet Flanagan at St. Luke’s gave me a break, I felt a responsibility to do that for other students.”

Minnick is now a professor in her alma mater’s communications department, which requires public relations and journalism majors to complete an internship. The experiences give students the opportunity to take the foundations and theories of their field and apply them to real-life situations, Minnick says. As interns, students practice what they’ve learned, see how a business works, discover what it takes to be a professional, develop portfolio pieces and network.

Similar to Minnick, some of her students have gotten jobs based on their internships.

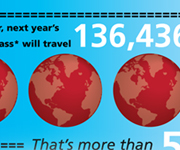

Approximately one out of five Northwestern students do an internship through their academic department or off-campus programs like the Chicago Semester or American Studies Program in Washington, D.C. Some internships—like those for the communications, exercise science and criminal justice programs—are mandatory; others are strongly encouraged by professors; still others are the result of a student’s own initiative. That 20 percent figure doesn’t include students required to do field experiences for majors like ecological science and Christian education, social work majors who must complete a 400-hour practicum, and education majors who spend up to a semester in the classroom student teaching.

Internships are less common in the sciences. Instead, Northwestern’s biology and chemistry professors encourage their majors to apply for summer research positions at major universities, when students have the uninterrupted time needed for science research.

“Internships in chemistry and biology tend not to lead to job offers, but more often help students make decisions about their career plans,” says chemistry professor Dr. Tim Lubben. Among those decisions: whether to attend graduate school, what area of chemistry or biology to go into, and whether to do research or practice medicine.

Kelley Salem ’09 spent a summer in a University of Iowa research program and is now at Iowa working on a doctorate in free radical and radiation biology.

“It really confirmed that I wanted to learn how to set up a research project and then see it through,” she says of that summer. “Undergraduate research is about learning techniques. I wanted to take that next step and actually try to solve a problem.”

Salem says her summer research experience paid a stipend and played an important role in her admission into graduate school. “They look at your [graduate test] scores and your grades in your science classes, but they also want to know what kind of research you’ve done,” she says. “I did my summer research with the co-chair of the bioscience program I got into, so I think that played a huge role in my admission because he got to see what I was capable of doing.”

Computer Whiz

Dustin Bonnema ’07 found his unpaid internship during the Chicago Semester a great way to prove himself. During the four months he spent in the Windy City, the finance and management major was placed with an investment firm, MainStreet Advisors, where his supervisor discovered he had some technological know-how.

The company was spending $10,000 per year on a client relationship management (CRM) database that had become so cumbersome they stopped using it. Because Bonnema had taken computing classes at Northwestern, he was tasked with creating a new CRM database for the firm.

“I built a database so they would have better contact management and just a better tool—something much more user-friendly that could be maintained in-house,” he says. “I actually modeled it after several databases I built in college.”

MainStreet Advisors still uses the database today—and Bonnema still maintains it. He was offered a job with the company at the end of his internship just prior to his graduation from Northwestern.

Most internships are completed during a student’s junior or senior year. By that point, says Bill Minnick, students have taken enough classes in their major that they can benefit their internship site.

Some students, like Bonnema, enjoy the flexibility of an internship scheduled just prior to graduation. Such timing provides the freedom to accept a job offer if one is made at the conclusion of an internship. Other students benefit from a junior-year internship, when they can apply what they learned in the work world to their final year of classes—or pursue new co-curricular activities they’ve discovered will benefit their future career.

Northwestern students can earn from 2 to 12 semester hours of internship credit, each hour of which requires 53 at the internship site. The responsibility for finding an internship lies with the student—something that is great practice, Minnick says, for finding a real job. “It’s really the student who needs to demonstrate the skill, ability and know-how to do well in their interview and land the internship.”

The Career Development Center requires students to fill out an application, identify 10 potential internship sites, provide references, and submit a resume and transcripts. Once an internship site is secured, Minnick works with the student and his or her professor to develop a learning contract outlining the student’s goals and objectives for the internship. Students must journal about what they are learning during their internship, do industry-related readings, have weekly one-on-one meetings with their on-site supervisor, and write a 7- to 10-page reflection paper at the conclusion of the internship.

Such requirements make an impact, says Professor Ann Minnick. “The internship site supervisors for my students tell me they’re impressed with the Northwestern internship program because students are receiving credit, they’re writing papers, they’re journaling, they’re doing extra readings, and they are accountable to someone at the college. They have to get a certain number of internship hours in per credit. It’s part of their rigorous academic program.”

An internship’s similarity to a job search was not lost on David Goodoien ’08. The political science and economics major was interested in international affairs, macroeconomics and diplomacy when he began researching internships online. He found one at the State Department for the fall semester of his junior year.

“They’re competitive, especially in the summer,” he says of the State Department positions. “Not all students can take a whole semester off. I was very fortunate to arrange my schedule so I could.”

Goodoien worked in an economic policy office, conducting current events research for high-level diplomats and helping plan an event hosted by then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. His internship, he says, was “validating.” Working with other interns from top schools around the country, he discovered that Northwestern had provided him with a good education and prepared him well.

Like Kelley Salem, Goodoien found his internship provided an edge for getting into graduate school: a master’s program in international affairs at Texas A&M University. “Everyone has a good GPA, the right degrees and a decent writing sample when applying for graduate school,” he says. “What they don’t have is experience that shows this is the career field they really want.”

Dogged Applicant

Chelsey Bohr ’11 is a prime example of the payoff initiative can have. Knowing undergraduate psychology internships are hard to get due to patient privacy issues, Bohr applied to nearly 100 treatment centers all over the country. She found a position in Utah that offered a stipend and room and board at a residential treatment facility for youth. During her summer internship, Bohr rotated through the facility’s different programs, helping with equine and recreational therapy, participating in group therapy sessions, and staffing the group homes.

“The most important thing I learned is that clinical psychology is the field I want to be in,” she says. “I was pretty sure before, but it’s one of those things that until you’re exposed to it, it’s pretty difficult to know.”

Now in a master’s program in clinical psychology at Emporia State University in Kansas, Bohr just landed another internship with a local mental health center.

“One of the things the woman interviewing me brought up was my undergraduate internship at a treatment facility. She understands how difficult they are to get, especially when working with clients, so it demonstrated the ambition and determination I had.”

Sometimes it takes more than a student’s initiative to land the perfect internship, however. Sometimes it’s a matter of who you know, your contacts, and the value of networking. Lindsey (Haskins ’10) Philips found that out when the South Dakota native was looking for a summer internship in 2008.

When everything she applied for fell through, it was a classmate’s father who came to the rescue. He took her resume to a meeting of development directors in the state. A family friend recognized her name and recommended Philips to her colleague at the South Dakota Community Foundation.

Ann Minnick’s years of experience in public relations have supplied her with numerous contacts she can call on to help her students secure internships.

“I tell my students they have a tremendous responsibility when they do their internship to represent Northwestern well, because if they do a good job, that internship site will be open to someone after them,” she says.

MARGOT SCHULMAN

Greta Hays’ internship at the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts opened doors to positions with theatres in Connecticut and Washington, D.C.

Skilled Networker

“Professor Minnick always said, ‘It’s about who you know,’” says Greta Hays, a public relations major who graduated from Northwestern in 2011. “She is so right! You can be great at what you do, but if you don’t know the right person, your chances are slim.”

Hays was one of 20 students out of 500 applicants who landed a prestigious semester-long internship at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. The Chicago native’s dream of a career in arts management was helped by the Kennedy Center connections—and reference letters—of her Northwestern theatre professors, Jeff and Karen Barker.

During her internship, Hays contacted publicists with different theatres, asking to meet for coffee and talk about their work. It was during one of her “coffee dates” that she heard about a fellowship program at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. Now in that fellowship, she puts into practice everything she learned in her Northwestern public relations classes—writing press releases, pitching stories, scheduling interviews with actors, and coordinating special performances for the media.

When her fellowship ends at the conclusion of this summer, Hays will be looking for work. To prepare for her job search, she’s networking, scheduling more coffee dates with theatre publicists in D.C.

Good internship experiences don’t happen by accident. The best, says Bill Minnick, provide students with practical, real-world tasks or projects. They offer a broad range of experiences and exposure to different parts of the company. They have a site supervisor who is monitoring and giving the intern valuable feedback.

“I tell my students they are privileged to have an internship, because it’s hard for a company or organization to accommodate someone who—even though they have an education—is still learning,” says Ann Minnick.

Dustin Bonnema, the former intern at MainStreet Advisors, is now supervising interns. Being on the other side of the relationship, he says, is eye-opening. “You start to realize how much is actually involved in teaching an intern. You have to make sure you’re putting in the time and effort to make it a worthwhile experience for everyone.”

Indeed, a good supervisor can have a life-changing impact on those he or she mentors. While interning at the National Center for Refugee and Immigrant Children, Elizabeth VanOort ’09 saw women in positions of power and leadership who were passionate about their work. She has since earned a master’s degree in social change from the Iliff School of Theology and is moving to Dallas to work with that city’s immigrants and refugees.

Ben Aguilera ’12 spent two summers interning with Pastor Jon Brown at First Reformed Church in Oak Harbor, Wash. Once only interested in youth ministry, Aguilera now feels called to the role of a senior pastor and will enter Western Theological Seminary this fall.

DAN ROSS

Zach Dieken’s dream of becoming an Iowa state trooper got a boost from his internship with the Lyon County Sheriff’s Department this spring.

Future Officer

People sometimes think of interns only getting coffee and doing filing. Zach Dieken’s internship was as far from that stereotype as one can get.

During his spring semester internship with the Lyon County Sheriff’s Department, Dieken trained with a SWAT team, spent time with dispatch, worked in the jail, went out on patrol, and helped with searches and arrests.

The hours that the sociology major from George, Iowa, spent with law enforcement officials fulfilled the requirements for his criminal justice concentration. They also helped him obtain a job in the Iowa State Patrol, based in Des Moines.

Ann Minnick tells her students that if they get a paid internship, “that’s icing on the cake.” They are “green,” learning, and an internship is part of their education—part of developing and honing their abilities and getting some work experience.

Internships don’t benefit only the intern, however. The Principal Financial Group in Des Moines, Iowa, has a robust paid internship program. The company hired 150 interns this summer, and its chairman, president and CEO, Larry Zimpleman, was once an actuarial intern for the firm.

The Principal has four employees who work exclusively with interns. Molly Cope is among those who build partnerships with universities and colleges in order to recruit, hire and train interns. The students, she says, bring energy and fresh ideas to the company. “We definitely embrace the diversity of perspectives that comes from bringing in new talent. And we look at our intern pool to fill our entry-level full-time positions.”

“They treat their internships as a long interview for a full-time position,” says Jacob Vander Ploeg ’12, who interned with Principal last summer and joined the firm May 21 as an actuarial assistant. “Once they hire somebody as an intern, it’s an indication they’re interested in you, and then you’re in a good position to prove you would fit in well with the company.”

Lindsey Philips interned with Lawrence & Schiller in Sioux Falls after her summer with the South Dakota Community Foundation and is now a public relations specialist for the advertising and marketing agency. She says the extended interview is a two-sided coin. “The employer can see how you work with people and the quality of work you do,” she says, “but as the student, you get to ask yourself, Is this really what I want to do? Do I enjoy this culture of this workplace?”

Philips and Northwestern’s Career Development Center director both agree internships give students a huge advantage when they are searching for a job.

“It’s a big benefit,” Bill Minnick says, “especially in today’s economy. If a job candidate search is down to two people and one has done an internship and the other one hasn’t, employers will go for the one with the experience.”

Internships are a chance to apply classroom learning to the working world, gain experience for a resume, and prove to an employer you’re the person to hire.

Internships are a chance to apply classroom learning to the working world, gain experience for a resume, and prove to an employer you’re the person to hire. Junior Jeriah Dunk and his band, Unique, use rap music to witness to God’s love.

Junior Jeriah Dunk and his band, Unique, use rap music to witness to God’s love. The miles traveled from home to campus are only part of the story as alumni reflect on their winding paths to NWC.

The miles traveled from home to campus are only part of the story as alumni reflect on their winding paths to NWC.

Classic Comments

All comments are moderated and need approval from the moderator before they are posted. Comments that include profanity, or personal attacks, or antisocial behavior such as "spamming" or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. We will take steps to block users who violate any of our terms of use. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. Comments posted do not reflect the views or values of Northwestern College.