Warrior for Women

Social work professor sheds light on domestic abuse that doesn’t bruise but still does damage

by Tamara Fynaardt

“He got the trash from the curb and carried it back into the house. He slashed the bags and dumped the contents on the floor. Then he dropped a gallon of milk on it, which exploded, and said, ‘Clean it up.’ I was on the floor, mopping and mopping—wiping really fast so he’d stop screaming at me. And I thought, ‘What am I doing? Why am I down here?’” ISABEL

Dr. Valerie (Roman ’93) Stokes listened as Isabel* described that moment among the garbage as the one when she knew “I need to get out.” (*Names have been changed for confidentiality.)

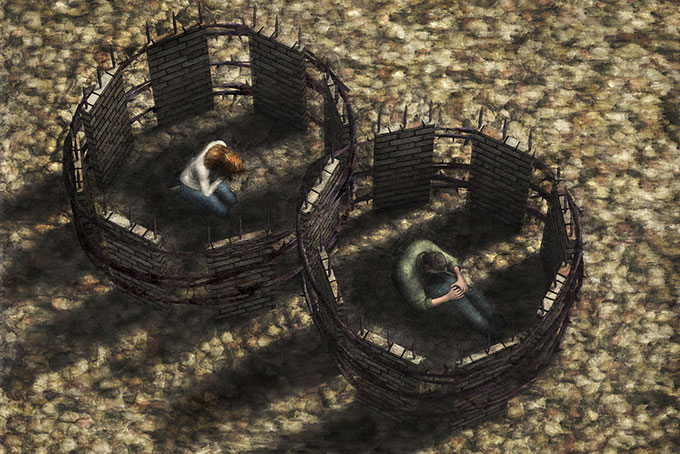

For every Isabel, there are many more women who stay. They secretly remain in relationships that may not be physically violent but can be just as damaging.

“These women suffer alone, in their homes. There aren’t any bruises, so no one notices. There is a war on women, and it’s real,” Stokes says—and she’s the kind of person who runs toward the front lines.

A social work practitioner before she became a Northwestern professor in 2008, Stokes has been behind the locked doors and closed curtains. Her career has included serving as director of a women’s and children’s shelter in Orange City and social worker for victims of sexual assault and domestic violence in Sioux City. She’s ridden with cops in squad cars and been summoned to the emergency room during the night to support girls who have been raped.

STEPHEN ALLEN

Dr. Valerie Stokes’ recent dissertation research on a form of domestic violence called Intimate Coercive Control enabled her to interview battered women in northwest Iowa—and then share their stories with students in her Violence Against Women class.

The Global War on Women

Last spring, Stokes taught a social work special topics class, Violence Against Women. Over the course of the semester, she and her students learned about the plight of women from Sioux County to Sub-Saharan Africa.

A main text for the course was Half the Sky, by married New York Times correspondents Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, an acclaimed book that makes the case, in graphic detail, that women worldwide really are involved in a war.

Kristof and WuDunn interviewed girls and women around the globe who told first-person stories of sexual enslavement, rape as a weapon of war, and community-sanctioned killings of women accused of promiscuity.

The authors wrote about their travels through developing countries where girls are denied education or adequate healthcare due to cultural convention or poverty so extreme that families are forced to fund school and vaccines for only their sons.

They also documented women who, against enormous odds, have had the temerity to build schools, stand up to Taliban bullies, and defy traditions that disfigure and devalue women.

Social work junior Carly Rozeboom volunteers at The Bridge women’s shelter in Orange City and dreams of working with women in Africa. Reflecting on the course, she said, “I knew that women’s rights was an issue near to Dr. Val’s heart, but I wasn’t personally aware of how serious and widespread [oppression of women] is.

“Women in Third-World countries are fighting for education or dying because they can’t get decent maternity care. Others living right next door might be suffering abuse. They all deserve to be treated better.”

Her classmate, sophomore Kaela Prachar, adds, “This is not just a gender issue. It’s a human issue.”

“I loved that work,” she says. “I loved the strength of the women, the sisterhood. We were taking care of each other. I resonated with the Old Testament prophets when they would cry out, ‘Injustice!’ It felt like that’s what I did.”

A soft-spoken, fiercely passionate advocate for people who are vulnerable, Stokes has taken her propensity to mentor to the classroom. Now a step removed from the raw reality of her early career, Stokes instead prepares Northwestern’s 50-plus social work majors for the front lines: to be listeners, hand-holders, voices shouting for justice on behalf of silent victims.

Two years ago, though, Stokes’ dissertation research gave her the opportunity to be in the fray again—hearing and sharing war stories that few people notice or acknowledge.

Stokes’ doctoral scholarship researched a type of domestic abuse labeled Intimate Coercive Control (ICC)—or, as it’s been called, “intimate terrorism.”

“The salient feature is control,” she says—control that’s wielded through threats of violence or violation, relentless criticism or other verbal abuse, and isolation through denial of access to money, transportation, or friends or family outside the home.

Stokes’ fliers, posted in northwest Iowa shelters and domestic violence centers, brought 12 rural women out of the shadows to tell their tales of intimidation and feeling trapped.

All mothers, ranging in age from 21 to 60, the women were from varying ethnicities and socioeconomic situations. “There’s no profile for the abused woman,” says Stokes, “as much as we want there to be so we can have a sense of security. We want to think, ‘It won’t be me. It won’t be my daughter.’ You want to know what kind of woman could be a victim of domestic abuse? Look in the mirror. She’s just like you.”

One of Stokes’ subjects, Mary, has been married for 39 years. Her husband is a business owner and respected community leader. She knows he makes a comfortable living, although she isn’t allowed access to their savings or checking accounts and has to ask him for money—and then provide a receipt—when she buys anything, including groceries.

Stacy’s ex-partner called her names and threw things. He constantly called her at work and demanded to know what she was doing and who she was talking to. Jamie’s partner kept her financially dependent, and once, when she angered him, he took her kids and disappeared for two months.

Ariel ignored her husband’s outbursts and the time when he broke her phone to keep her from calling anyone. But the one time he vented his frustration with his fist, cracking her cheekbone, she knew she had to leave—if not for herself, at least for her daughter. “I heard her crying, and her first words were, ‘Is Dad going to kill you?’ That’s when I [told myself] ‘You know, this [isn’t right]. [S]he isn’t going to live hearing this.’”

Stokes’ research focused on moms to explore whether mothering had any effect on women’s inclination to seek help. It did. As with Ariel, nearly every woman in Stokes’ study was convinced either by her children or because of them to leave the abusive situation.

Tragically, leaving an abusive home for the sake of one’s children can lead to losing them. Iowa and Minnesota, for example, have laws that classify witnessing domestic violence as child abuse. So a mother brave enough to tell authorities she’s been the target of abuse can find herself “relieved” of parenting by Child Protective Services.

“A lot of women are scared that I gonna ask for help and they gonna help me a little bit too much and take my children away,” shared an abuse victim in a Journal of Emotional Abuse article Stokes cites in her dissertation. The women Stokes interviewed confirmed that laws like these are an obstacle to seeking help.

Another tragic irony, one that Stokes was pained to uncover, is that rural, religious communities can present unique barriers to emotionally battered women. There are practical obstacles—like distance from a shelter, counselor or other social service provider—and there are societal obstacles—when exposing one’s brokenness can lead to gossip and judgment.

“Because of my husband’s role in our community and church … very few people in our town would not know who we are,” says Mary, who traveled several towns over when she finally sought help. “I felt like I still had to protect his business and reputation—not make people feel uncomfortable.”

Within rural communities, the church can be a safe place—or a place that sweeps messiness under the rug. “I value my Christian faith and traditions, so it was hard for me to hear what some of the women said about the ways Christian beliefs were misused in harmful ways,” says Stokes.

“My family is very religious,” Stacy told her, “so when I had struggles [with ICC], they were ashamed. They cut ties with me. My mother said, ‘You made your bed. Now you need to lie in it.’ Church leaders told me to submit to my husband, let him be the ruler of the house.” When Pam unburdened herself to Bible study friends, their advice and offers to pray for her felt dismissive. “They told me, ‘There’s sin in the world, so we have to suffer. You should stay in the relationship.’ That can be dangerous advice.”

Nonetheless, especially as governmental efforts to rein in spending have led to cuts in services provided through the Violence Against Women Act, the church could be one of the organizations to fill the gap. Some of the women Stokes interviewed have experienced the restorative healing a church family can provide for an emotionally bruised woman.

Daisy’s church is helping her finance counseling for her sons, and Linda’s helped her hire a lawyer. Jada’s pastor accompanied her to a protective order court hearing. “His sitting with her sent a message,” says Stokes. “It said he supported her. It said that courtroom was a place where a clergyman—where the church—should be. It helps when men, including clergymen, say and demonstrate that we won’t tolerate anyone mistreating women or viewing them as inferior.”

Stokes says that anyone can watch out for a woman who’s in trouble. Listen, she advises. “If her husband cuts her down in public, check with her. Let her know you heard him and ask if he says those things often—because if he says it in public, he probably says worse in private. We need to have the courage to care about each other.”

Courage, after all, is necessary in the midst of a war.

Whether it’s tulips planted on campus or bricks used to build the new learning commons, we have the facts and figures to satisfy your curiosity.

Whether it’s tulips planted on campus or bricks used to build the new learning commons, we have the facts and figures to satisfy your curiosity. Social work professor sheds light on domestic abuse that doesn’t bruise but still does damage

Social work professor sheds light on domestic abuse that doesn’t bruise but still does damage Life-changing accident doesn’t stop professor who loves learning

Life-changing accident doesn’t stop professor who loves learning

Classic Comments

All comments are moderated and need approval from the moderator before they are posted. Comments that include profanity, or personal attacks, or antisocial behavior such as "spamming" or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. We will take steps to block users who violate any of our terms of use. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. Comments posted do not reflect the views or values of Northwestern College.