The Radio Signal

Family members of Elizabeth Job, who would meet and marry Friedhelm Radandt after the war, listen to the news on a Philips radio. Both Elizabeth’s grandfather (front) and father (not pictured) worked for the Dutch electronics firm Philips in Warsaw, Poland, where the latter was in charge of the development and manufacturing of radio tubes.

Today more people are living as refugees than at any time since World War II. In 1945, Friedhelm Radandt was one of them. The man who would serve as president of Northwestern from 1979 to 1985 was a boy of 12 when his family fled their home in Neustettin, Germany, to escape the advancing Russian army. Radandt's newly published book, The Radio Signal, tells the stories of his family and that of his future wife, Elizabeth, as they struggled to survive while staying true to their Christian faith.

As the book begins, Friedhelm's father, Ernst, is stationed in Italy with the German army; his 16-year-old sister, Gisela, is in another village serving as a nanny; and his 14-year-old brother, Ernst-August, has been drafted and is serving as a soldier with Germany's National Socialist Motor Corps. When the Russian army advances on Neustettin, Ernst-August brings Friedhelm, his mother, Gertrud, and his little sister to a public square where buses are waiting to evacuate a small, privileged group of people.

As soon as they were seated on the bus, Gertrud remembered the bag she had packed for her husband. In their hurry to evacuate, they had forgotten to bring it along.

"Your father's suitcase," she murmured. "We cannot leave it behind."

Gertrud didn't know if the Radandts would ever return to Neustettin or how much of the town would even survive the onslaught of the oncoming Russian soldiers. If Ernst were going to have any personal effects when he returned from the war, they would have to go back for that suitcase.

The officer in charge at the Hindenburgplatz assured her that, despite the apparent hurry, they still had plenty of time.

Gertrud turned to Friedhelm. "I need you to go back for the case."

Feeling a rush of fear mingled with excitement, Friedhelm nodded. He hopped out of the bus and started half-walking, half-running back to his home.

He found the suitcase exactly where his mother had said it would be. Back outside in the bitter cold, Friedhelm placed the suitcase onto his sled and pulled it behind him through town, across the snow and ice.

Thoughts of the bus made him a little fearful. Where would the bus take them? What would become of his family? At least he wasn't alone. The war had a way of ripping families apart, and Friedhelm was thankful to have his mother, brother and younger sister close.

But when Friedhelm turned the corner into the Hindenburgplatz, the square was empty and utterly silent. The icy, deserted street glistened in the moonlight.

The buses were gone.

Friedhelm was just three months old when Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany and the Nazi Party came into power. With a growing family, Ernst Radandt takes a part-time job with Kraft durch Freude (KdF), an organization designed to help build the German economy. The KdF also encourages the purchase of a Volksempfänger, or people's radio, so Hitler and the Nazi Party can reach into the homes of as many Germans as possible. Ernst does well in his job—even purchasing a Volksempfänger radio for his family—and as a result, is offered a promotion. But first he must complete a questionnaire detailing his lineage in order to prove his Aryan descent. He also must help identify the town's Jewish shop owners and join a troop of Nazis in parading them around town while calling on its citizens to boycott Jewish businesses.

But [Ernst] could not bring himself to persecute the Jews. His faith wouldn't allow it. It was clear to him that the Bible's dictates were not compatible with what the Nazis asked of him.

He had to decide whether to be true to his Christian faith or to actively support the anti-Semitic stance of the Third Reich.

[Ernst] felt a tingle of fear for himself and for his family, but he had no doubt about what to do. He left the questionnaire incomplete and told the Nazis he didn't want their job.

As for what would come next, Ernst could only put his trust in God.

Ernst's decision results in reprisals. He loses his job. Needing to make a living and to provide safety for his family, he joins the German army—the one part of German society that maintains some autonomy from the Nazis—and is stationed in Neustettin as a recruiting officer. Then, one Sunday, while worshipping with other Christians in their home, the Radandts hear two Nazis knocking on their door.

Ernst knew these Nazi officials would not look kindly on any meeting in the home of someone who had already stood in opposition to their party.

He was not doing anything wrong, he reminded himself as he slid closed the pocket doors to the living room. He was amazed at his friends in the prayer group. They sat so still behind those pocket doors that the house seemed completely empty.

"Good afternoon," he said to the Nazis as he unlocked the front door.

"Good afternoon, Herr Radandt. I wonder if we might have a word with you. We want to talk to you about your sons. Ernst-August and Friedhelm. They are very impressive boys. The Hauptjungzugführer who heads up the local Jungvolk has spoken very highly of them. We have no doubt Ernst-August will do very well when he matriculates to the Hitlerjugend later this year."

"Thank you," Ernst told them. All boys were required to become members of the paramilitary Hitler Youth upon their 14th birthdays. Ernst didn't like it, but he said the words he was expected to say. "He is lucky to have the opportunity."

"On the contrary: We are lucky to have him. He's a brave and clever boy. We also took the liberty of looking into your younger son, Friedhelm. Quite a bright and alert little boy, isn't he? You must be very proud."

"Indeed I am," Ernst answered.

"Are you familiar with the Napola schools?"

Ernst nodded. The Nationalpolitische Lehranstalt, Napola for short, were military boarding schools created by Hitler to produce future leaders steeped in Nazi ideology.

"We would very much like your boys to join us as cadets. We think that with the right education, your sons will grow into great men."

Ernst considered carefully how to reply.

"It is a great honor for your sons to be invited to the Napola," said the one in charge. "But if it is too much of a hardship to relinquish both of your boys, then give us the younger. Give us Friedhelm."

Because, Ernst knew, it is easier to indoctrinate a younger boy.

"No," he told them. "No, I will not. These are my sons, and I am responsible for their education."

The two Nazis looked at one another. They weren't used to being turned down. "Are you quite sure?"

"My sons will not attend your school."

The Nazis stood [to leave]. "That is a regrettable answer, Herr Radandt—as you will no doubt discover."

Friedhelm’s future wife, Elizabeth, and her siblings get a ride in the two-wheeled wagon used to transport their few belongings from barracks where they had lived as refugees.

Because of his refusal to send his sons to Hitler's boarding schools, Ernst receives word he is to be stationed on the Eastern Front. But thanks to a friendship with a high-ranking military officer, he is instead assigned a desk job in Italy. It is while Ernst is in Italy that Friedhelm is left behind when his family is evacuated from Neustettin. The boy heads north on foot, away from the approaching Russian army, and is eventually reunited with his mother and little sister. Older sister Gisela, in the meantime, has her own experience with Russian troops.

[Gisela] had been sitting with the Schütze family for an early lunch when she first noticed their silverware rattling gently against the china, vibrating, so it made a jingling noise.

Mr. Schütze asked for everyone to be quiet, and they all watched as the shaking grew stronger. Soon the whole table was rattling, and the vases on the nearby shelves too.

Then he walked to the window. Across the field, a line of tanks was rumbling up the road.

The adults gathered up the children as quickly as they could, with nothing but the clothes they'd been wearing, and ran out the back door. Mr. Schütze aimed the family toward a line of trees on the north end of the estate.

Until they reached the trees, at least a quarter-mile away, there was nowhere for them to hide. If any of the soldiers came to the back of the house, they would see the Schützes. And if the soldiers saw them and gave chase, there would be no way to outrun them.

Gisela had heard rumors. The advancing Russians had become known as Stalin's "army of rapists." The leaders of the Red Army hoped that inflicting a thorough campaign of humiliation and fear upon the German people would deter any threat of future invasions of the Soviet Union, and they encouraged their soldiers to be as violent and terrifying as they liked.

And there they were now, pouring out the back door of the house.

Half a dozen Russian soldiers watched from the veranda as the desperate family plodded through the heavy snow. One of them took aim with his rifle and fired. Gisela heard the hiss of the bullet pass by her head before she even heard the report of the gunshot.

Mrs. Schütze stumbled in the snow.

"Get up," Gisela told her. "We have to keep going."

"Where?" Mrs. Schütze cried. "There is nowhere to go!"

"The lake."

Though the lake that bordered their property had been frozen most of the winter, a temporary thaw had turned the upper layer of ice into slush, and there was no way to know how thick or strong the remaining ice was. But the family didn't have a chance of escaping the Russians across the field. The lake offered a shorter and faster route, albeit a more dangerous one.

"I'll go first," Mr. Schütze said. "I'm biggest. If the ice will hold me, then it will hold any of you."

The family followed him out onto the lake, doing their best to follow in his footsteps.

Gisela picked up the youngest child in her arms. She heard the ice groan under her feet, stressed by the added weight of the child, and she stopped in fear, listening for any cracking sound that might indicate the ice was failing.

She didn't know where to take her next step. The slush was too uneven; there was no way to guess the state of the ice underneath.

Then she heard the voices of the Russian men behind her, and she steeled her resolve. It's better to fall through the ice, she thought to herself, than to wait here and be captured. She took a step, and then another, until she reunited with the rest of the Schütze family at the line of trees along the far side of the lake.

The Russians stood at the opposite bank, watching the fleeing family and stepping their feet tentatively onto the frozen slush. Deciding it wasn't worth the risk, they turned around and went back into the house.

Gisela and the Schützes were safe—for now.

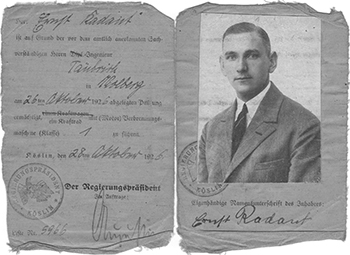

Friedhelm’s 14-year-old brother, Ernst-August, as a soldier in the National Socialist Motor Corps.

The war again catches up with Friedhelm, his mother and little sister, who have taken refuge in Kolberg with Gertrud's parents. With the city surrounded by the Russians, the family boards a small boat under cover of night.

The boat slipped quietly out of the dock and into the cold, black water of the Baltic Sea. When they were about a mile from shore, it lined up next to a large freighter. One by one, the passengers climbed up a ladder to the freighter's deck, and from there, they were shepherded below deck.

[Gertrud's] father had already climbed several steps down the stairs leading into the storage area below, but she grabbed hold of her son and daughter. The three of them found a discreet spot on the main deck, out of everyone's way, where they huddled under blankets and waited for the ship to lift anchor.

It was an hour before the ship started moving westward. The churn of its engines drowned out the noise of the distant artillery, but as Friedhelm looked back to the silhouetted skyline, he saw something he would never forget: The Russian tanks and artillery surrounding the town had begun a coordinated attack. There were flashes of light from all sides. The bombs cascaded down, and within minutes, the entire town of Kolberg was engulfed in a huge fireball. The city burned fiery orange against the coal-black sky.

Beside him, Gertrud felt a sob well up in her chest but choked it back down, determined to stay strong for the sake of her children. She was grateful her father was not on deck to see this. His life, his home, his legacy, even his wife's grave so freshly dug in the sand—everything he'd ever known was burning, destroyed by the flames.

In the waning days of the war, Ernst Radandt's unit is called back to Germany. Scanning his office one final time before heading out, Ernst discovers a sack of mail delivered that day—and in it, miraculously, letters from both his wife and his oldest daughter telling him where they had found refuge. After Germany surrenders, Ernst is reunited with his wife and learns from Ernst-August's former commander that the Radandts' oldest son is trapped in Russian territory. Ernst sends word he will be waiting for Ernst-August on the British side of the border.

[Ernst-August] woke just before sunrise and ran west toward the border until he had a clear view of the Russian watchtower and the bridge. On the other side he saw a small hut he assumed must be manned by British guards.

He prowled along the lakeshore, working his way toward the bridge, hiding among the trees. But he couldn't imagine any way to make it across the long bridge without being seen—and shot—by the Russians.

When he reached the bridge, he went flat on his stomach and started to crawl. He was sure that at any moment the guard in the watchtower would see him and shoot. Three-fourths of the way across, he jumped up and made a dash for the hut, but the hut was empty.

Ernst-August would have to make another dash. He stayed put for several minutes, catching his breath, and then he ran, not stopping until he was in the cover of the trees. From there he found his way to the road that led into the next village.

The Russian guard never even called out.

Far up the road, he could make out the shape of a man walking toward him. It was a shape he would recognize anywhere.

"Dad!" he called out, as he ran up the road. It was his father. Ernst-August could barely believe his eyes. "How did you find me?"

"You're my boy." Ernst threw his arms around his son. "I'll always find you."

The two of them shared a hug while the sun came up. Then his father started walking up the road toward Ratzeburg.

"Where are we going?" Ernst-August asked.

Ernst threw an arm around his boy. "We're going to get your sister. And then all of us are going home."

Friedhelm Radandt, now retired, served as a college president for a quarter of a century, first at Northwestern College and then at The King's College in New York. After immigrating to the United States with his wife, Elizabeth, whom he met following the war, he earned graduate degrees at the University of Chicago and enjoyed a teaching career at that institution and at Lake Forest College. He now lives in Seattle. The preceding excerpts were condensed from Radandt's book, The Radio Signal. You can read the rest of his story—as well as the harrowing tale of his wife's family's escape from Warsaw, Poland—in the paperback or Kindle versions of the book, both available on Amazon.com.

A book by former president Friedhelm Radandt tells of his childhood experiences as a refugee in Nazi Germany during World War II.

A book by former president Friedhelm Radandt tells of his childhood experiences as a refugee in Nazi Germany during World War II. New Director of Christian Formation Mark DeYounge talks about what the next generation needs in worship and spiritual guidance.

New Director of Christian Formation Mark DeYounge talks about what the next generation needs in worship and spiritual guidance. Relationships that began 19 years ago in Colenbrander Hall have remained strong, thanks to a technology that wasn’t around back then—Google Hangout.

Relationships that began 19 years ago in Colenbrander Hall have remained strong, thanks to a technology that wasn’t around back then—Google Hangout.

Classic Comments

All comments are moderated and need approval from the moderator before they are posted. Comments that include profanity, or personal attacks, or antisocial behavior such as "spamming" or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. We will take steps to block users who violate any of our terms of use. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. Comments posted do not reflect the views or values of Northwestern College.