Lab Work

Only a select few colleges and universities have been accepted into the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s SEA-GENES research program. Northwestern is one of them.

BY ANITA CIRULIS

LEM MAURER

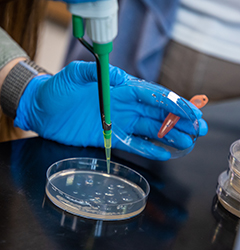

Sammy Blum (left) and Ali Almail were two of the first students to take the research-focused SEA-GENES lab from Dr. Sara Tolsma, professor of biology.

Earn a biology degree from Northwestern, and you’re virtually guaranteed to graduate with research experience.

Five years ago, Northwestern was one of 20 colleges and universities accepted into the 2016–17 cohort of SEA-PHAGES, a national program designed to interest undergraduates in scientific research. Now nearly 150 institutions are part of a global effort to discover phages, or viruses that infect bacteria.

SEA-GENES is the next step in that research. Five colleges and universities in the U.S. were part of the first cohort selected for SEA-GENES. Eight—including Northwestern—were selected for the second cohort in 2020.

“There are so many more opportunities for research,” says Dr. Sara Sybesma Tolsma ’84, professor of biology, of the impact of the program. “You don’t have to be the top of the class with all this extra time. You just take a couple of courses, and you’re doing it.”

Those courses are SEA-PHAGES: Discovery, a two-credit lab in which students discover and isolate phages; Genetics and Genomics, a four-credit course in which they annotate phage genomes; and SEA-GENES, a two-credit lab in which they identify the functions of phage genes.

SEA-PHAGES comes with financial support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science Education Alliance. “It’s not a grant, but we get thousands of dollars’ worth of supplies—such as enzymes and primers—from them,” Tolsma says.

Each school in the SEA-GENES program is assigned a phage to research. Northwestern’s is named Island3.

“We’re cloning all 76 genes and then asking if any of those genes cause the host bacterial cell to die or grow more slowly—and if any prevent another virus from infecting the host cell,” Tolsma says.

Three students were enrolled in the inaugural SEA-GENES lab last fall: seniors Ali Almail and Sammy Blum and junior Lauren Pavich.

Blum, who graduated in May and is now enrolled in Northwestern’s physician assistant graduate program, gained an appreciation for what research involves. “I didn’t realize how much critical thinking and team collaboration goes into research,” she says.

Pavich—who will serve as Tolsma’s teaching assistant this fall—also enjoyed the collaborative nature of the class, citing times she, her classmates and Dr. Tolsma would have discussions about how to move forward when something wasn’t working.

LEM MAURER

In SEA-GENES, students clone the genes of a bacteriophage as a step to determining their function.

“I enjoy research a lot,” she says. “I wasn’t very good at critical thinking before coming to Northwestern, but these programs have definitely made it easier to learn how to work through problems.”

Almail was grateful for the opportunity to search for answers to questions raised when he took Genetics and Genomics. He applied and was accepted into Northwestern’s Junior Scholars program, which allowed him to continue his search for a sequence of DNA, referred to as a “promoter,” that turns a gene on or off.

“He’s gotten some amazing data,” Tolsma says of Almail. “We think we’ve characterized a promoter that’s never been characterized before.”

For this year’s national SEA Symposium, the conveners considered more than 80 abstracts for talks. Almail was one of five students chosen to discuss their research results. He isn’t, however, the only Northwestern student with results to share from their research. Since Northwestern was accepted into the SEA-PHAGES program, more than 50 of the college’s students have produced peer-reviewed publications to add to their resumes.

Almail will begin studying at the University of Toronto’s medical school this fall and someday hopes to be a pediatric doctor and researcher. The majority of Northwestern’s biology department majors are interested in just practicing medicine, but Tolsma says research experience is invaluable for them as well.

“This helps them in their role as clinicians,” she says. “They’ll be better able to interpret scientific evidence and to more critically evaluate research that might impact their patients.”

Ultimately, the research conducted through the SEA-PHAGES and SEA-GENES programs aligns with Northwestern’s goals to be a place where people use their minds to better understand, serve and love God’s world.

That’s what faculty and students do in the SEA-PHAGES and SEA-GENES courses. Instead of canned labs and an emphasis on memorization, students experience real science that involves solving problems, interpreting data and thinking critically.

“I’m excited. I’m interested. I’m curious,” says Tolsma of the phage research taking place at Northwestern. “And when I look at the students, they’re excited, they’re interested and they’re curious. Both of those things give me life.”

Only a select few colleges and universities have been accepted into the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s SEA-GENES research program. Northwestern is one of them.

Only a select few colleges and universities have been accepted into the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s SEA-GENES research program. Northwestern is one of them. Northwestern makes preparing students for success and meaningful work central to its mission.

Northwestern makes preparing students for success and meaningful work central to its mission. Trick-shot artist garners millions of followers on TikTok.

Trick-shot artist garners millions of followers on TikTok. National runner-up season seems taken from the big screen.

National runner-up season seems taken from the big screen. Family celebrates two graduates during Northwestern commencement.

Family celebrates two graduates during Northwestern commencement.

Classic Comments

All comments are moderated and need approval from the moderator before they are posted. Comments that include profanity, or personal attacks, or antisocial behavior such as "spamming" or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. We will take steps to block users who violate any of our terms of use. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. Comments posted do not reflect the views or values of Northwestern College.