New Year, Improved You

Psychology alum’s research offers promise for healthy behavior change (and maybe some success with your New Year’s resolutions)

BY TAMARA FYNAARDT

About half of the population makes New Year’s resolutions. We want to exercise more. Eat less. Get rid of a bad habit and gain a good one. A Google search, “How do I keep my New Year’s resolutions,” returns more than 24 million results linking to sources from the American Psychological Association to a blog by Mamaguru, all offering tips, tricks and tactics for making resolutions and—the harder part—keeping them.

There’s plenty of advice because there’s an abundance of failure. The same sources cite dismal success rates for keeping New Year’s resolutions: around 8 percent, maybe as high as 20, but that’s as good as it gets. By February, most of us are back to acting like it’s 2017.

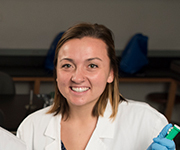

Dr. Amanda (Brown ’07) Brouwer doesn’t usually make New Year’s resolutions. But she is interested in both enabling people to change their behavior and then helping them sustain that change. Her health psychology research in a relatively new area of study, the self-as-doer identity, was published this past fall by Routledge, a global publisher of academic scholarship.

In the preface of Brouwer’s book, Motivation for Sustaining Health Behavior Change: The Self-as-Doer Identity, she recounts the genesis of what has become her research passion: a Northwestern course with psychology professor Dr. Jennifer Feenstra. “I was reading in my health psychology textbook about things I’ve experienced and thought about personally as someone with Type 1 diabetes,” Brouwer remembers. “I thought, ‘This is fascinating! I want to know more.’”

RON REGAN

Dr. Amanda Brouwer, who teaches and collaborates on research with students at Winona State University, recently published her research on how self-as-doer identity theory can help people set self-care and other healthy goals and stick to them.

Brouwer joined Feenstra’s research lab, learning how to create a study and collect and analyze data in preparation for her senior psychology research project. Brouwer wanted to see if an identity theory known as self-as-doer could promote healthy self-care behaviors among people with diabetes, a condition she has had since age 12.

Step one: Find 100-plus people with diabetes. “It was kind of a tricky population to find as an undergraduate,” Brouwer explains, but a Sioux Center diabetes educator Brouwer knew had contact with a medical device representative who sold insulin pumps. Brouwer was able to email his client list and ask for volunteers for her study.

She then asked her volunteers to list goals for good diabetes self-care—like checking one’s blood sugar and taking insulin. Participants also offered goals such as resisting chocolate and eating fruit. Next she asked them to identify the action in each goal and turn it into a word with an “er” suffix, making it into a self-as-doer phrase: blood sugar checker, insulin taker, chocolate resister, fruit eater.

“No matter how linguistically easy it seems—just adding the “er” suffix—the key thing that sets it apart from a stagnant goal is that the doer gets motivation from connecting the goal to actual behavior, creating a mental image of oneself doing the goal,” Brouwer explains. “It seems easy, but that’s why I love it. It makes sense to people.”

Finally, Brouwer’s study participants rated themselves on a scale of one to five (one being “does not describe me well at all” and five being “describes me very well”), indicating how closely they identified with their self-as-doer phrases.

“The results indicated that self-as-doer identities could predict self-care behaviors,” says Brouwer. People who saw themselves as chocolate resisters were more likely to follow through than those who hadn’t made that particular self-care behavior part of their identity.

“I was so excited!” Brouwer says. “Anytime your research actually discovers something, it’s like, ‘Woo hoo!’ That’s what really drove me to graduate school—I fell in love with the research end of psychology: asking questions, seeing how we could answer them, and figuring out what to do if the answers lead to more questions.”

Using her Northwestern senior thesis as a pilot study, Brouwer expanded her self-as-doer research in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She categorized her Northwestern study participants’ more than 500 unique doer phrases into a standardized list of doer statements describing good diabetes self-care: for example, I’m a blood sugar checker, an insulin taker, a physical activity doer, a healthy eater.

Then Brouwer spent a year surveying more than 300 people with diabetes and analyzing their responses. Her results demonstrated a predictive relationship between high self-as-doer identities and good diabetes self-care. “Those who saw themselves as blood sugar checkers, insulin takers, physical activity doers and healthy eaters were seven times more likely to have a good hemoglobin a1c, which is a measure of one’s control of her or his diabetes,” Brouwer explains.

For her doctoral dissertation, Brouwer decided to test the efficacy of the self-as-doer identity on a non-clinical population, one that wanted to be healthier—like dieters—but didn’t have the medical motivation of having to manage their chronic illness or suffer the consequences.

After recruiting volunteers who’d expressed an interest in eating healthier, Brouwer divided them into three groups. The control group simply recorded their diet four times a week. A second group received information describing healthy eating behaviors and then also recorded their diet four times a week. The final group also received nutrition information and then Brouwer guided them through the self-as-doer exercise. She helped them identify healthy eating goals and then create self-as-doer phrases, making themselves the actor of those goals: leafy greens eater, whole grains consumer. Then she asked them a series of questions aimed at helping them visualize what a “leafy greens eater” looks like and identify actions they could take to enable more regular eating of leafy greens.

At first, the majority of all the participants ate healthier foods. “Even the control group knew they were participating in a diet study, so they paid attention at first and chose healthier foods,” Brouwer says. “A difference showed up after about a month. Those in the third group who’d had the self-as-doer intervention were maintaining their healthier diet. Those who hadn’t done the self-as-doer exercise had regressed back to their pre-study diets.”

Now a tenured psychology professor at Winona State University in Minnesota, Brouwer teaches undergraduate courses in social and health psychology and is continuing her self-as-doer research with the help of students in her own research lab. She wants to test a self-as-doer intervention similar to the one she explored with people who wanted to eat healthier, this time with volunteers who want to be more physically active. She expects that study will get fully under way next school year when she’s on sabbatical.

If you try self-as-doer on your own goals for 2018, Brouwer would like to know how it goes. Tell her about your experience: abrouwer@winona.edu.

After that, she wants to return to clinical populations. Can self-as-doer help other patients with chronic illness like it does for people with diabetes? Would the results be similar for people with hypertension or HIV/AIDS?

“I have so many questions!” she says. “Enough to spend a lifetime doing research.”

JESSICA SANDS

Amanda Brouwer’s self-as-doer research informs her family life as she and her husband, Scott ’06, strive to be healthy eaters and at-home meal-makers.

Self-as-Doer DIY

So far, Brouwer’s research has focused only on physical health behaviors, including diet and exercise. But she says the theoretical background for her research and the studies she’s done suggest self-as-doer has possibilities for enabling people to make and sustain change in other areas of well-being too, like emotional, spiritual or relational health.

So get out your New Year’s resolutions and give it a try.

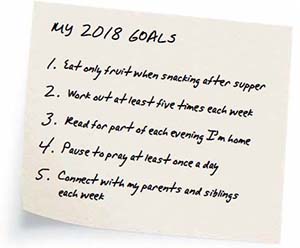

STEP 1: List your goals

Write down your goals. They should be personal, specific and, if possible, positive. For example, instead of a goal to “stop eating junk food,” a positive goal aimed at the same outcome might be to “eat more fruits and vegetables.” A more specific version would be to “make fruits and/or vegetables half of any meal I eat” or “eat only fruits or vegetables when snacking after supper.”

Or say your goal is to “spend less time on social media.” You might abandon pursuit of your goal more quickly if you don’t come up with something else—something positive—to do during the time you’re hoping to be unplugged. So instead of “spend less time on social media,” your goal might be to “read during part of every evening.”

You can write down as many goals as you want, but Brouwer recommends starting with no more than six goals as a manageable number.

STEP 2: Create your self-as-doer phrases

Turn each of your goals into a self-as-doer phrase by describing the person who does the goal—you. Each phrase should include a word with an “er” suffix that identifies what you, the doer, will do. Brouwer says it’s OK if some of the phrases are awkward or grammatically questionable (she and her research subjects laughed about some of their phrases like “size 8 jeans wearer” and “more vegetable fitter inner”). It’s most important that the self-as-doer phrases be meaningful to you personally.

STEP 3: Measure your identification with each self-as-doer phrase

For each self-as-doer phrase, rate how well it currently fits you, using this scale:

1 – Does not describe me well at all

2 – Does not describe me well

3 – Neutral

4 – Describes me well

5 – Describes me very well

STEP 4: Make the necessary changes so you can become the person described by your self-as-doer phrases

For each self-as-doer phrase for which your score is three or less, visualize yourself as that doer and think about what it would take for you to become the person described by that phrase. For example, if “weekday exerciser” doesn’t describe you well, why not? What do you need to change so it could describe you? Perhaps you need to switch your gym membership to a facility closer to work so you can go during the noon hour. Or maybe you need better fitting, more stylish work-out wear so you feel more confident going to the gym or running in your neighborhood.

To be a daily, thoughtful pray-er, it might help if you kept your church newsletter on your bedside table so you can pray meaningfully for any members listed. Or you might commit to praying over one national or international need after you watch or read the news each day.

STEP 5: After four to six weeks, measure your identification with each self-as-doer phrase again

Hopefully your scores have improved and you are on your way to the point that your new healthy behaviors have become not only sustainable habits, but they’ve also become part of your self-concept. You are a person who snacks on fruit while reading to wind down each evening (because you get up earlier now in order to work out). You touch base with your parents and siblings at least once each week to find out what’s going on in their lives (and you pray well-informed prayers for them).

For any self-as-doer scores that remain below three, go back to the first step and reflect on how committed you are to that goal. Consider trying a different, but related, goal and go through the rest of the steps again until you’ve become more of the person you want to be.

A research interest that started at NWC has led to psychology professor Amanda Brouwer’s first book and offers help for those who want to get healthy and stay that way.

A research interest that started at NWC has led to psychology professor Amanda Brouwer’s first book and offers help for those who want to get healthy and stay that way. Participation in pioneering study helps Northwestern students explore careers as research scientists.

Participation in pioneering study helps Northwestern students explore careers as research scientists. Alumni share stories about the best things they found in their campus mailbox.

Alumni share stories about the best things they found in their campus mailbox. 6 Questions with Scott Simmelink

6 Questions with Scott Simmelink

Classic Comments

All comments are moderated and need approval from the moderator before they are posted. Comments that include profanity, or personal attacks, or antisocial behavior such as "spamming" or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. We will take steps to block users who violate any of our terms of use. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. Comments posted do not reflect the views or values of Northwestern College.